Soil Structure Secrets: Grow Thriving, Vibrant Gardens

Have questions about soil structure? Soil Health and Sustainable Soil Management expert Deirdre Griffin-Lahue joins Erin Hoover to talk about why soil structure matters and to share practical tips on how we can improve our soil structure

Episode Description

In this episode of The Evergreen Thumb, host Erin Hoover interviews Deirdre Griffin-LaHue, an expert in soil health, about the importance of soil structure in gardening. They discuss how soil structure—how mineral particles and organic matter form aggregates—affects water retention, air flow, and plant health. Deirdre explains the difference between soil texture and soil structure. Key tips include protecting soil with mulch or cover crops, adding organic matter to feed beneficial microbes, and avoiding compaction by not working the soil when it’s too wet or dry.

Deirdre Griffin-LaHue is an Associate Professor of Soil Health and Sustainable Soil Management at WSU’s Northwestern Washington Research & Extension Center (NWREC) in Mount Vernon. Her integrated research & extension program focuses on the impacts of agricultural practices on soil’s physical, chemical, and biological properties, how these properties interact, and how to tailor soil health assessments to the Pacific Northwest’s soils and cropping systems. Her research interests focus on the impacts of agricultural practices on soil microbial communities and the functions they provide.

Listen Now

Resources on Soil Structure

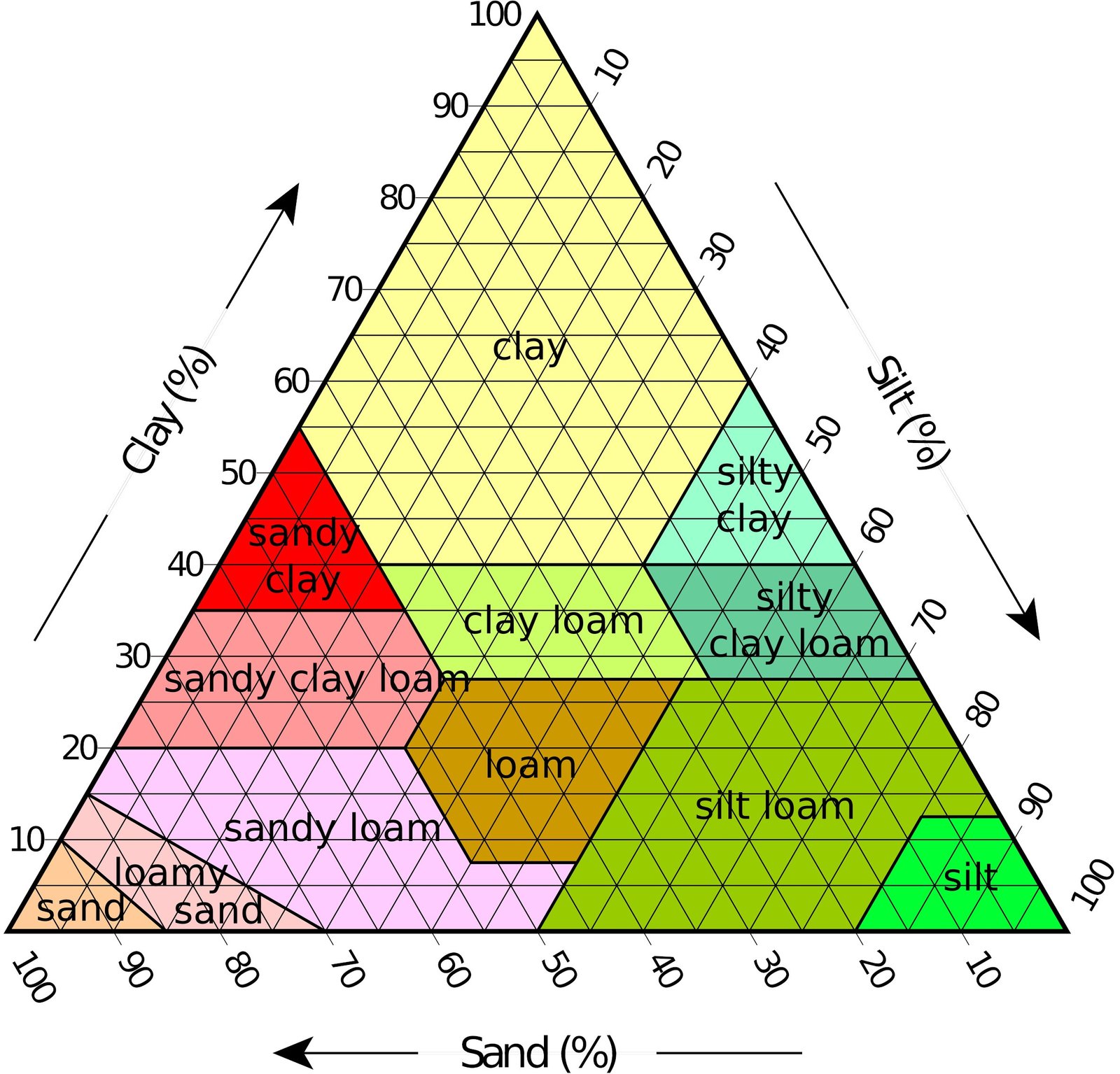

Soil Texture Triangle

Slake Test

This top view shows how the soil on the left started to fall apart while the soil on the right stayed in a ball.

Slake Test

This side view shows the cloudiness of the water on the left, and how the water on the right is.

Transcript

[00:00:00] Erin Hoover: Welcome to The Evergreen Thumb, episode 60. My guest today is Deirdre Griffin-LaHue, and she is an associate professor of Soil Health and Sustainable Soil Management at the WSU Northwest Research and Extension Center in Mount Vernon. She’s here today to talk to us all about soil structure.

Thanks for joining me today. Welcome to the show.

Deirdre Griffin-LaHue: Thanks for having me.

Guest Introduction

Erin Hoover: So, can you tell us a little bit about yourself and the work that you do at WSU?

[00:00:27] Deirdre Griffin-LaHue: Sure. So, my name is Deirdre Griffin-LaHue, and I am an associate professor of Soil Quality and Sustainable Soil Management, which is a mouthful, but I’m based at the WSU Mount Vernon Research and Extension Center, and I focus on soil management across a variety of systems, particularly in Northwestern Washington.

[00:00:49] But I work statewide helping farmers kind of optimize their soil management for improved soil functioning and improved crop productivity. I think about, you know, what makes our soils healthy and in different contexts, how can we best manage them?

What is Soil Structure?

[00:01:06] Erin Hoover: Today, we’re going to talk about soil structure. Can you tell our listeners a little bit about what soil structure is and what it means?

[00:01:14] Deirdre Griffin-LaHue: So soil structure is a very important component that we look at in terms of, um, understanding how a soil is going to function. And so basically a soil structure is how components of the soil, uh, like the mineral components sand, silt, and clay and organic matter piece together to form structures or aggregates that can then influence how much pore space there is in the soil, the size of the pores that are in the soil, which really influence how that soil’s going to behave.

Why is Soil Structure Important?

Erin Hoover: You kind of alluded to it, but why is soil structure so critical to trying to grow a garden?

Deirdre Griffin-LaHue: As I mentioned, soil structure is going to influence pore space.

[00:01:52] So when you look at a soil and if you consider, you know, a whole soil is a hundred percent, about 50% of that in an ideal case is going to be pores, and some of those pores are going to be filled with air and some are going to be filled with water. Um, and the other 50% is your mineral components of the soil and your organic matter.

[00:02:11] So, you know, if you think about having 50% of the soil being pore space, it’s really on that soil structure component too. To define what that pore space is. And, and it’s not just about total pore space, but it’s about kind of what size pores do you have. Um, so for example, if you have a really sandy soil, um, and you have don’t have much soil structure, you’re going to have a lot of large pores that, you know, water’s going to flow really quickly through that soil.

[00:02:45] But if you have soil structure in your sandy soil, it’s going to allow for some more really small pores that can help hold onto water, can help microbes live in them, can help protect organic matter. And on the flip side, if you have, let’s say, a really clay soil, a lot of people think about really heavy clay soils as being heavy, um, and having very little pore space.

[00:03:08] Actually, clay soils have a lot of pore space, but they tend to be, if there’s not good soil structure, tend to be very, very small pores and not very many big pores. So, um, you know, you might have, it might be very waterlogged. There might not be much airflow, might not be much room for roots to grow, but if you have soil structure where those clay particles are kind of bonded together into little, what we call aggregates, which are like little pea sized structural units, then they actually can create more of those larger pores that can allow water to flow through air to flow through roots to grow.

[00:03:42] So that’s where that soil structure comes in and kind of defining how much pore space you have and kind of what distribution of pore sizes that you have. And it’s nice to have a, a lot of pores of all different sizes.

The Importance of Air in Soil Structure

[00:04:00] Erin Hoover: You mentioned that a lot of those pore spaces are taken up with air. Can you explain the importance of air as a function of the soil structure?

[00:04:07] Deirdre Griffin-LaHue: Yeah. We definitely want a good airflow in our soils. Roots and microbes in the soil for the most part, need oxygen. So roots need oxygen to grow a lot of the microbes in the soil. Microbes tend to be aerobic, meaning they use oxygen just like we do.

[00:04:26] They’re breaking down organic matter. You know, those plant residues or sugars that are in the soil and they need oxygen to be able to do that. And so if you don’t have good airflow into the soil, you’re going to have low oxygen. It’s going to shift what organisms are there and it can really shift nutrient dynamics in the soil.

[00:04:48] So we want good airflow for those roots and for those beneficial microbes in the soil.

Soil Texture vs. Soil Structure

[00:04:55] Erin Hoover: What is the difference between soil texture and soil structure?

[00:04:57] Deirdre Griffin-LaHue: Yeah, so I’ve talked a little bit about sand, silt, and clay, and the difference between a sandy soil and a clay soil. So, soil texture is the distribution of sand, silt, and clay in your soil.

[00:05:11] And so it’s just kind of those relative sizes. The differences between sand, silt, and clay are the size of the particles. So it’s just talking about the mineral part of your soil, the sand, silt, and clay percentages. And if you are familiar with the texture triangle, that’s how you determine your, your soil texture.

[00:05:31] You can send your sample into a lab and they’ll measure how much sand, silt, and clay is in your soil. You can also try to feel it with your fingers, and there’s some flow charts that you can use to estimate what kind of soil you have. But the main thing is that soil texture is not impacted by management.

[00:05:54] Soil texture is kind of an inherent property that is due to, you know, what type of rocks your soil formed from, um, how that material got there, how long it’s been acted upon by, you know, our, our climate. Um, which is usually, you know, hundreds of thousands or millions of years. So it’s not something that you can change with management unless you are importing soil from somewhere else, which you may be doing in a backyard garden.

[00:06:18] So soil texture does not change. It does not get impacted by organic matter, but soil structure does. And knowing your soil texture is very important for knowing how to manage your garden in terms of nutrients and in terms of soil structure.

[00:06:39] Erin Hoover: I live in the Chehalis River Valley, so it’s a lot of glacial outwash, which means we have very rocky soil.

Deirdre Griffin-LaHue: Yeah.

Erin Hoover: So how does that fit into the soil texture in the, like, the web soil survey? Ours is, it’s Chehalis gravelly loam.

[00:06:53] Deirdre Griffin-LaHue: Mm-hmm.

[00:06:54] Erin Hoover: Um, so we do have a little bit of loam, but it is so fast-draining because it’s got those large pores from the large rocks. So the water, it just, it doesn’t hold water very well.

[00:07:05] Deirdre Griffin-LaHue: Yes. Great question. So when we’re thinking about soil texture, kind of the, the first part of it is what we consider the less than two-millimeter fraction. So, for the, at the beginning, we kind of ignore all of the things that are more than two millimeters.

[00:07:23] Um, and so we’re, the biggest thing we’re thinking about is sand or coarse sand. So when you look at that texture triangle as you’ve observed, it doesn’t say anything about gravels or rocks or cobbles. So the base of it is that kind of less than two-millimeter fraction. But then we also of course need to know, okay, well, what we call them, course fragments in the soil science world.

[00:07:47] You know, what kind of course fragments do we have? What is there above two millimeters? And that includes, you know, small gravels and includes, as you go bigger in size, cobbles or boulders. So it’s important to know what kind of size, uh, those are. So gravelly is a certain size class, and then if it reaches a certain kind of percentage, that’s when you get those modifiers to your texture class where it says a gravelly loam or a cobbly loam.

[00:08:17] Um, or sometimes you get a very gravelly loam. That’s when it kind of reaches a certain percentage. And of course, that is really gonna affect things like nutrient and water holding capacity.

The Effects of Soil Structure Damage

[00:08:27] Erin Hoover: So what are some of the ways that soil structure can be damaged, um, and what effect does that have on the, our ability to grow plants in that soil?

[00:08:35] Deirdre Griffin-LaHue: When you’re working in a garden or in a, uh, topsoil, you’re most likely gonna be seeing what’s called a granular soil structure, meaning that there’s kind of those pea-sized aggregates in a well-structured soil. Those are held together fairly well by organic matter, and I can talk a little bit more about how those form, but they can get damaged by, you know, heavy, uh, rainfall.

[00:08:59] For example, if you don’t have a cover on your soil. If it’s just exposed, especially in the winter in our part of the world, you know, those heavy rains can really disperse the soil particles and create, you know, crusting or create clogging of the soil pores. So heavy rainfall in an uncovered soil can definitely disturb soil structure.

[00:09:28] Disturbance can disturb soil structure. Um, especially a lot of soil structure and some soils can be held together by like fungal hyphae. And if you have a lot of soil disturbance, those hyphae are not gonna be able to, to grow and proliferate. So that can impact soil structure. And so, it’s important to think about if you are disturbing the soil and, and sometimes we need to, but think about how wet is the soil when I’m doing this, or how dry is it?

[00:09:55] If it’s very wet or very dry, you’re more likely to damage your soil structure. This might not be relevant to a garden situation necessarily, but the weight of the equipment that you’re using, or if you’re standing on the soil while you’re, uh, using a shovel or using a, a, a fork, um, you know, the, your weight, if the, particularly if the soil’s wet, can cause compaction and cause that soil structure to get, you know, squashed and all the pore space to get pushed out.

[00:10:25] So thinking about your weight or the weight of any equipment that you’re using, especially if the soil is particularly wet, that can cause damage.

How to Protect Garden Soil from the Elements

[00:10:34] Erin Hoover: So in like a vegetable garden then, so like mulch or um, cover crops, things like that would be things that would help protect it from those heavy rains that we often get in the winter.

[00:10:45] Deirdre Griffin-LaHue: Exactly, yeah. So especially over the winter, um, using a mulch, whether that’s like a straw mulch or, or wood chips or something like that, a straw mulch can work well in a garden situation. That’ll just help protect the, the top layer of soil from that beating, pounding rain that we get.

[00:11:06] Or like you mentioned, cover crops can also be really helpful. They can also help take up water so that the soil is not so saturated as it does tend to get in our part of the state.

[00:11:15] Erin Hoover: Aside from, like aside the weight of equipment or of people on the, on the soil, what are some other ways that, uh, disturbance can break down those pores or those aggregates?

[00:11:26] Deirdre Griffin-LaHue: Yeah, so the, the weight or the equipment coming in and just breaking them apart.

[00:11:32] So, you know, those are the main ways, ways to promote it or help the soil be more resilient would be, um, increasing the organic matter content, increasing, um, the ability of, of microbes to break down, uh, organic matter you’re putting in. So, um, soil aggregates or soil structure is formed, um, in large part by microbes in the soil.

[00:11:57] They are, you know, when they break down, you know, if you put compost in or a cover crop or, um, root material, they’re eating that up. And part of what they’re doing is they’re putting out these sticky substances that can help, kind of almost like create bungee cords to help bind particles together.

[00:12:19] I also mentioned fungi.

They can help with kind of wrapping around soil particles and organic matter to create more stable, um, aggregates. So, ways to, you know, even if you do need to disturb the soil, which we, as I mentioned, we sometimes do, making your soil structure a little bit more resilient by increasing that organic matter, uh, feeding the microbes that are in the soil, that can be really beneficial to not having as much compaction or disruption of the structure.

[00:12:48] Erin Hoover: I know we kind of have a common joke in our master gardener group that “when in doubt add organic matter”.

[00:12:55] Deirdre Griffin-LaHue: Yes. Yeah, I think organic matter and you know, it can look, it can be in different forms based on what works well in your system or what you have access to. Organic matter, adding organic matter feeding the soil is just a, a great way to help improve soil functioning generally.

[00:13:11] Erin Hoover: You mentioned root material. And that made me think about, that’s, uh, a lot of times we encourage, I like what I do in my garden is corn. I’ll just chop it off at the soil level. Leave those roots there. So that they can, the microbes can break that down over the winter and gives them food and adds the, the porosity in the soil.

[00:13:31] So, um, that’s kind of what made me think of that.

[00:13:35] Deirdre Griffin-LaHue: Absolutely. Yeah. Dead roots and living roots are really valuable. There’s good research that living root material is extremely valuable for building organic matter, feeding microbes. And like you mentioned, having those dead roots as well, and those root channels can, as they break down, that’ll help with your soil structure as well.

Best Practices to Avoid Compaction

[00:13:55] Erin Hoover: You kind of touched on this, but what are some of the best practices to avoid compaction? You talked about, you know, walking on softer soils and, um, trying to avoid that, but what are some other ways to avoid compaction?

[00:14:06] Deirdre Griffin-LaHue: Like I mentioned, pay attention to how wet or dry your soil is.

If it’s too dry, it can kind of fracture apart really easily.

[00:14:13] If you think about holding kind of a dry aggregate and squeezing it, it’ll just kind of burst. And so that can happen if the soil’s too dry and you’re working it similarly, like I mentioned, if it’s too wet, um, it’s just really easy for it to smush together.

Another thing that’s, um, important to think about is if you maybe are on a slightly larger scale and are using, uh, maybe a walk behind rototiller or some other, uh, equipment where you’re kind of working the soil to the same depth all the time.

[00:14:43] You can sometimes get compaction down at that particular depth. In agriculture, we call it a plow pan, where basically you’re fluffing up the soil above it, but you are continuously kind of pushing down the soil, maybe a foot down, and you can get this really compacted layer down at that depth.

[00:15:05] And so that can really restrict root growth. You might have really nice soil on the top six inches or 12 inches, but then your roots hit that layer, and they just go sideways because they can’t get through that. So a good way to tell if you have compaction down at depth is, I mean, you can dig a, put a shovel in of course.

[00:15:23] Or if you have like a wire flag, that can be a good way to kind of push it into the soil and see do you hit a resistant layer? A lot of times, of course in our, our home gardens, you know, there’s, when the house was being built, there could have been a lot of compaction that occurred as they, you know, cleared the lot and leveled the land.

[00:15:44] So, I know in my garden we have some serious compaction at a foot just because of, um, you know, when the lot was put in. So that’s something that home gardeners definitely grapple with.

The Role of Organic Matter in Soil Structure

[00:15:55] Erin Hoover: Can we talk a little more about the organic matter and the role that it plays in the structure of soil?

[00:16:00] Deirdre Griffin-LaHue: So organic matter is made up of, you know, dead plant material and a lot of soil biology, either living or dead soil biology.

[00:16:10] Um, and you can get organic matter, you know, being kind of those larger pieces of partially decomposed organic matter, but also you can have dissolved organic matter, which is really great for feeding microbes, and you can have organic matter that attaches directly to clay particles. So, when you get organic matter attaching directly to clay particles, it allows for more pore space between clay particles, and so that can be really valuable for that, really, you know, really, really small aggregates, uh, really, really small soil structure that can then be built upon.

[00:16:42] There are some great videos where people have gone really in depth, looking within a small aggregate at all of the different clay particles and really small bits of organic matter that are protected within it.

[00:17:01] And then, um, you can see sometimes, like I mentioned, those fungal hyphae wrapped around it. Um, so the, you know, the active part of organic matter, though, that microbial biomass, the living and dead microbial biomass attaching to mineral surfaces, kind of helps bind different particles together and create more resistant, uh, aggregates that are gonna be able to withstand more rain or more disturbance and, and keep their structure.

[00:17:31] Erin Hoover: Something I just thought of that kind of goes back to what we were talking about when the soil is too dry or too wet as a way to, uh, avoid compaction. A lot of times, gardeners are told to wait until the soil is workable, uhhuh. Um, but that’s kind of a vague descriptor. And so, how much water is too much to be able to work the soil?

[00:17:52] Deirdre Griffin-LaHue: Yeah, it’s a great question. It’s hard to have like one specific answer because of course the water content’s gonna vary by different soils. Um, but you know, a good rule of thumb is if we’ve just gotten a big rain, um, you want to be able to let the soil drain so that there’s not, you know, it’s not too saturated and preferably let it dry out a few days beyond that.

[00:18:22] I think, you know, a good way to test is to actually like reach into the soil and, and you know, pick it up and move it between your fingers and just kind of feel like as you do that, are you really smushing it down or is it kind of gently falling apart? Um, you know, are those, you can kind of feel the planes of weakness, I call them, between the soil aggregates and, you know, are you able to kind of get that, those planes of weakness just kind of gently falling apart?

[00:18:50] Or are you actually, as you move it between your fingers, are you kind of smearing it or smashing it and smushing those aggregates together? So can, it has to be a little bit of a feel thing, but it’s, it’s a really important consideration and a lot of the farmers I work with, you know, in the spring, they’re sitting and waiting for the soil to be workable because we get so much, it rain in the winter and it’s so wet in the spring.

[00:19:14] And you can do a lot of damage, especially on a larger scale, if you have heavy equipment, if the soil’s not ready. But I think, you know, in a home garden situation, really putting your hand in the soil, picking up a handful, breaking it apart, and seeing what it looks like.

How Living Roots and Soil Organisms Affect Soil Structure

[00:19:31] Erin Hoover: We talked a little bit about, actually, we’ve talked a fair amount about living roots and soil organisms. Can you expand a little bit more on how those directly affect the soil structure?

[00:19:41] Deirdre Griffin-LaHue: One thing that some microbes make, both bacteria and fungi, is what we call them, extracellular polymeric substances. So basically, it’s like sugars or uh, sugar proteins. They can act as glues. And, and so it’s by feeding those organisms, and you know, it’s hard to know exactly which organisms you’re feeding.

[00:20:06] And I’m kind of a generalist. I don’t, you don’t need to like, add specific microbes to the soil to have this happen. Just feeding the ones that are there and promoting them, um, will help. So, um, but they can create these extracellular polymeric substances that help, you know, create those bungee cords.

[00:20:27] And, um, our muscular mycorrhizal fungi also create proteins that do a similar thing. So one soil test that we’re starting to do more and more is actually measuring those proteins and um, it’s a nitrogen source, but people really think they’re really related to soil structure as well. So that can be, you know, on the soil health testing side of things.

[00:20:54] You know, we really think that those proteins that are created by microbes are valuable in helping water-stable aggregates form.

A Simple At-Home Soil Resilience Test

[00:21:04] Erin Hoover: Are there other, other factors on a, like a soil test when you’re looking at the results that might indicate how healthy the structure is?

[00:21:13] Deirdre Griffin-LaHue: Yeah. You know, soil structure, it’s a hard thing to measure in a traditional soil test.

[00:21:19] You know, I think your organic matter content can be helpful for kind of getting a sense. Your organic matter, combined with your texture, can give you a sense of how. That soil’s going to behave, but of course, it’s not directly measuring the soil structure. So a great thing to do that you can do at home is when the soil is kind of at that nice workable soil moisture, take a, you know, maybe a, a fist sized amount of it.

[00:21:46] Um, if you can find a piece that’s kind of, holding together. It can be smaller than that too, but maybe, you know, two or three inches, uh, across. You can take that and get a jar of, of water. And if you have a, like a mesh sieve at home, um, or if you have a, a bowl of water that you can put the mesh sieve in.

[00:22:06] Stick it in the, uh, stick the sieve into a bowl or jar of water and then put the clod on the sieve and you can see how much it disperses. So that’s similar to a test that we do in the field with farmers or we, um, have a slightly more advanced version that we do in the lab to compare between soils, but you can actually test how well that soil holds together when it’s put in water.

[00:22:33] And if you also like lift the sieve up and then put it back down, you know, you’ll see, does that water kind of moving out and into the aggregate, make it really fall apart. And we’ve done this with side by side, you know, fields that have been treated differently and you can really see one of them holds together really well when it’s sitting in water and the other just falls apart and the water gets really dirty and cloudy.

[00:22:59] So that’s a great thing to do at home. Just to kind of understand how resilient your soil structure is.

Practical Steps Gardeners Can Take to Improve Their Soil Structure

[00:23:07] Erin Hoover: So what are some practical steps that gardeners can take to, uh, improve their soil structure if it has been compacted or suffered in other ways?

[00:23:18] Deirdre Griffin-LaHue: Yeah, so I think, you know, if you do have compaction, what I would start with is getting organic matter in the soil.

[00:23:24] So, you know, finding a good compost source, for example, or growing a cover crop. Um, it’s getting a little late now to start growing a cover crop, but, um, you know, next year you could grow a cover crop or have something growing over the summer.

So getting organic matter in there and it’s okay to, you know, incorporate that organic matter into the soil even though you’re disturbing it.

[00:23:47] Um, just, you know, getting it into the soil, um, getting it, you know, accessible to the microbes that are in there can be a great starting place to kind of help rebuild the soil structure. And then as you go forward, you know, they’ll start breaking that down and you can try to, um maybe reduce some of the disturbance or think carefully about the timing of it.

[00:24:08] And like you mentioned, you know, having living roots in the ground is great. You know, maybe being strategic about if you are disturbing the soil, you know, how much are you disturbing the whole area or just one small part, um, so that organisms and, and roots can kind of, um, come back into that area that gets disturbed.

[00:24:29] Yeah, I think those can be good ways and just, you know, the first way to understand your soil is I think, really knowing what the texture is and what your organic matter content is, and that can be a good starting point to understanding how it’s gonna behave and what you might need to really be careful of.

[00:24:50] Erin Hoover: So once you have incorporated some organic matter and to try to help break that up and feed those organisms, I mean, obviously, you need to continue to add organic matter.

Deirdre Griffin-LaHue: Mm-hmm.

Erin Hoover: So they have something to feed. So, say like in a home garden situation, um, if you were to just top dress after you, after that initial turning it in, as your soil structure’s improving, top dressing, will the microbes and the, um, organisms pull that organic matter down into the soil?

[00:25:21] Deirdre Griffin-LaHue: Yeah. In a lot of cases, they will. Or you, as you get moisture or rain, some of it will dissolve and move into the soil that way with the water. And so I think that can be, top dressing can be a really good way to do that. It’ll be slower than, uh, incorporating it, but I think especially if you’re in a system where you have, you know, perennial plants, top dressing is a really good way to still add organic matter and, you know, earthworms can also help bring some of it down into the soil. So that’s a great solution.

[00:25:46] If you’re growing vegetables, you know, then it’s okay to incorporate it, uh, a bit before you plant your vegetables.

Final Thoughts About Soil Structure

[00:26:02] Erin Hoover: Any final thoughts you want to share about the soil structure?

[00:26:06] Deirdre Griffin-LaHue: I don’t think so. Yeah, I think we covered a lot of it. Um, but it’s definitely a great thing to pay attention to because it definitely affects how your soil functions and the health of your plant.

Erin Hoover: For sure. All right. Well, thanks for joining me today.

Deirdre Griffin-LaHue: Yeah, thanks for having me.

[00:26:24] Erin Hoover: Thank you for joining us on this episode of The Evergreen Thumb, brought to you by the WSU Extension Master Gardener Program volunteers and sponsored by the Master Gardener Foundation of Washington State.

We hope that today’s discussion has inspired and equipped you with valuable insights to nurture your garden.

[00:26:35] The Master Gardener Foundation of Washington State is a nonprofit organization whose primary purpose is to provide unifying support and advocacy for WSU Extension Master Gardener programs throughout Washington State.

[00:26:54] To support the Master Gardener Foundation of Washington State, visit www.mastergardenerfoundation.org/donate.

Whether you’re an experienced Master Gardener or just starting out, the WSU Extension Master Gardener program is here to support you every step of the way. WSU Extension Master Gardeners empower and sustain diverse communities with relevant, unbiased, research-based horticulture education.

[00:27:19] Reach out to your local WSU Extension office to connect with master gardeners and tap into a wealth of resources that can help you achieve gardening success.

To learn more about the program or how to become a Master Gardener, visit www.mastergardener.wsu.edu/get-involved.

If you enjoyed today’s episode and want to stay connected with us, be sure to subscribe to future episodes filled with expert tips, fascinating stories, and practical advice.

[00:27:46] Don’t forget to leave a review and share it with fellow gardeners to spread the joy of gardening.

Questions or comments to be addressed in future episodes can be sent to hello@theevergreenthumb.org.

The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed by guests of this podcast are their own and do not imply endorsement by Washington State University or the Master Gardener Foundation of Washington State.