Digging Deeper: Exploring the Link Between Geology and Soil Composition

Mark Amara, a retired soil scientist and current WSU Extension Grant-Adams Master Gardener joins us to talk about geology and soil composition.

Episode Description

In this episode of The Evergreen Thumb, our guest Mark Amara guides us through the fascinating connection between geology and soil composition. Mark gives listeners an overview of the geological history of our region before explaining which parts of our region have been most influenced by volcanic activity. He explains what coulees are and gives a summary of the Missoula floods and how they formed coulees. He discusses basic soil-forming factors and gives listeners an overview of The Columbia Basin Irrigation Project. Mark finishes the episode by explaining how to use the Web Soil Survey to determine your soil composition.

Mark retired with 30 years from the USDA NRCS in WA & OR where he worked as a Soil Scientist, Soil Conservationist & Cultural Resources Specialist. Since then, he has worked as a Food Alliance Farm Inspector Certifier evaluating dry land & irrigated row crop farms using sustainable agricultural practices and has worked as a professional archaeologist. He has been a WSU Extension Grant-Adams Master Gardener since 2007, and has a large vegetable garden, and has been a Volunteer Program Co-Coordinator since 2018. He co-authored a book on the geology of Grant County, WA & has written articles on geology, soils, farming, & gardening.

Listen Now to Geology and Soil Composition

Resources

- Washington Geological Survey | WA – DNR

- Ice Age Floods Institute

- Roadside Geology of Washington (A personal favorite book!)

- USGS: The Channeled Scablands of Eastern Washington (Geologic Setting)

- Web Soil Survey

- Museum Store | Moses Lake, WA – Official Website (find Mark’s book here)

- Digging Into the Basics of Soil Biology – Episode 12 – The Evergreen Thumb

- Pests, Predators, and Prevention: Integrated Pest Management for Vegetable Gardens – Episode 017 – The Evergreen Thumb

- Beneath the Blooms: Creepy Garden Critters with Todd Murray – Episode 007 – The Evergreen Thumb

Transcript of Geology and Soil Composition

[00:00:00] Erin Landon: Welcome to Episode 20 of the Evergreen Thumb. My guest today is Mark Amara. Mark is here today to talk to us about the link between geology and soil composition. He retired after 30 years from the United States Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service in Washington AND Oregon where he worked as a Soil Scientist, Soil Conservationist, and Cultural Resources Specialist.

Since then, he’s worked as a Food Alliance Farm Inspector Certifier evaluating dry land and irrigated row crop farms using sustainable agricultural practices and as a professional archaeologist. He’s been a WSU Extension Master Gardener volunteer in Grant Adams counties since 2007 and the volunteer program co-coordinator since 2018.

He co-authored a book on the geology of Grant County, Washington, and has written numerous articles on geology, soils, farming, and gardening.

Before we join Mark, let’s jump into the May gardening calendar.

May Gardening Calendar

So working on planning in May, it’s a good time to prepare and prime your irrigation system for the summer months.

You can use a soil thermometer to help you know when to plant vegetables.

Wait until the soil is consistently above 70 degrees to plant warm-season plants like tomatoes, squash, melons, peppers, and eggplants. May is also a good time to place pheromone traps in apple trees to detect the presence of Codling moths and to plan a control program of sprays, baits, and or predators when the moths are found.

For maintenance, it’s a good time to fertilize rhododendrons and azaleas with an acetate fertilizer. if it’s needed. If they are established and healthy, their nutrient needs really are minimal. It’s also a good idea to remove the spent blossoms. If you’re looking to select new roses for your garden, choose plants labeled for resistance to diseases.

Fertilize roses and control rose diseases such as mildew with a registered fungicide. In planting and propagation, it’s a good time to plant dahlias, gladioli, and tuberous begonias about mid-month depending on your climate. And you can also plant chrysanthemums for fall color. And it’s also a good time to get started with some planting in the vegetable garden.

Depending on where you are and when your last frost day is, you can start getting into brassicas, squash, peppers, and things like that, beans. It’s gonna depend, at least in Western Washington, most people wait until Mid to late May, Mother’s Day to Memorial Day to put peppers and tomatoes in the ground.

For pest monitoring and management, if an unknown plant problem occurs in your garden, contact your local WS Extension Master Gardener program. If you are unsure of how to contact them, call your county extension office and they can get you in touch with the appropriate people.

Managing weeds while they’re small and actively growing with light cultivation, um, makes them much easier to manage. If the weed goes to bud, they’re going to seed. It’s going to be a lot harder to manage them, but also they have a more substantial root ball. So you’ll be losing more soil, than if you pull them out when they’re small.

Leaf rolling worms may affect apples and blueberries, so prune off and destroy any affected leaves.

Monitor aphids on strawberries and ornamentals. If present, control options include washing off with water, hand removal, or using registered insecticide labeled for the problem plant. Read and follow all label directions prior to using any insecticide. Promoting natural enemies such as predators and parasitoids that kill or eat the insects is a longer-term solution for insect control in the garden.

Spittlebugs may begin to appear on ornamental plants as they foam on stems. In most cages, Spittlebugs don’t require management. You can wash them off with water or use an insecticidal soap as a contact spray. Just be sure again, to read and follow the label directions. Other insects like Cabbage Worms, and Cucumber Beetles can be controlled by hand removal, placing a barrier over newly planted rows such as a screen or a row cover.

Again, Root Maggots in cole crops like broccoli and cabbage, again with row covers, can help prevent infestation.

Monitor rhododendrons, azaleas, primroses, and other broadleaf ornamentals for adult Root Weevils. You can do this by looking for fresh evidence of feeding, which is notching at the leaf edges.

Try sticky trap products on plant trunks to trap weevils. Protect against damaging the bark by applying the sticky material on a 4-inch wide band of poly sheeting or burlap wrapped around the trunk. Mark the plants now and then manage with beneficial nematodes when the soil temperatures are above 55 degrees.

If Root Weevils are a consistent problem, consider removing plants or choosing more resistant varieties.

Control slugs with bait or traps, and by removing or mowing vegetation near garden plots. Monitor berries such as blueberries, raspberries, and other soft fruits for Spotted wing drosophila. Learn how to monitor for Spotted wing drosophila, flies, and larval infestations in fruit.

A good source reference for any sort of pest management is HortSense, and I will link to that in the show notes. You can look up by the plant or by what you believe the insect to be. And now let’s turn over to Mark.

Introducing Our Guest

Mark, thanks for joining me today. Welcome to the show.

[00:05:46] Mark Amara: Well, thank you. I’m glad to be here.

[00:05:49] Erin Landon: Um, why don’t you tell us a little bit about yourself and your experience in soils and geology and with WSU?

[00:05:58] Mark Amara: Okay, um, I’m gonna, I’ve been gardening for almost 50 years. I’ve got a small organic hobby farm and I’ve been a Grant-Adams Master Gardener since 2007. For part of my career with the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, I was a soil scientist mapping soils in Washington and Oregon, and I co-authored a book on Eastern Washington geology.

My background in soils and geology has helped me relate to farming and gardening management strategies and explain the geology of the region to the general public.

An Overview of the Geological History of Washington

[00:06:41] Erin Landon: So can you give us kind of an overview of the geologic history of Washington and how that has kind of influenced the current landscape?

[00:06:50] Mark Amara: Sure. Well, the short answer is that the geologic history of Washington has been influenced by plate tectonics, mountain building, folding and faulting, and erosional and depositional events over billions of years. The long answer is somewhat more complicated. There were at least a dozen pieces of the crust floating on the molten mantle around the world.

Here in Washington, two plates, the continental plate, or the North American plate, and the oceanic, or Pacific plate, are continually colliding. If you can envision it, the oceanic plate is thrusting below the continental plate, which is sinking back into the mantle. Where the plates come into contact, it’s always associated with a flurry of earthquakes and volcanic activities.

Around a billion years ago, give or take a couple hundred million, the edge of the continental or North American plate was along the east edge of Washington state, which means that everything to the west was in the ocean, or along the coast. Sediment accumulated and became sedimentary rocks there for at least 800 million years.

Then around 200 million years ago, the plates began shifting again. The shifting margin of the coastline sunk further as the continental and oceanic plates collided, and a band of metamorphosed folded sedimentary rocks known as the Kootenay Arc formed in the Blue Mountains in Southeastern Washington, as well as creating granites in Western Montana, Idaho, and Northeastern Washington.

Volcanoes in the Cascades were active until about 25 million years ago. It’s a little bit complicated, but there was more activity as shifting plates of the North American continent sunk into the mantle and magma pooled in the Okanogan Valley to form the Okanogan Highlands or erupted from cracks or fissures in the earth’s crust to form the Columbia Plateau.

Pieces of the continents continued to reshape Washington into what is referred to as the North Cascades microcontinent, which merged with the crust to shape Washington and British Columbia. The present Cascade Mountains are relatively recent, having formed in the last couple of million years. West for the Cascades, sediments, and soils formed in oceanic crust materials, which are contrasted with the Olympic Mountains, which formed from a material that was uplifted and consists of folded crustal sediments.

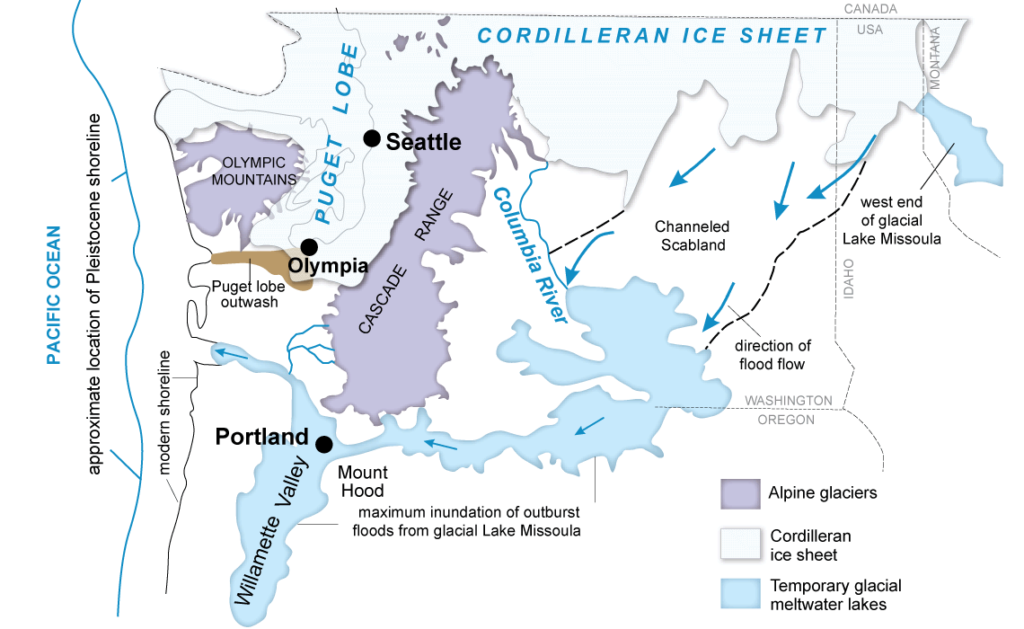

The Willapa Hills and Puget Lowlands in Western Washington are blanketed with glacial deposits from advances and retreats of the continental glaciers, which occurred four to six times in the last two million years. Eastern Washington tells a similar tale, except that the glaciers did not advance as far south as in Western Washington.

As the mountains rose, the climate became drier in Eastern Washington.

Areas Most Influenced by Volcanic Activity

[00:09:53] Erin Landon: So you kind of lightly touched on, you mentioned volcanic activity, but um, are there particular areas of Washington that were more influenced by volcanic activities than others?

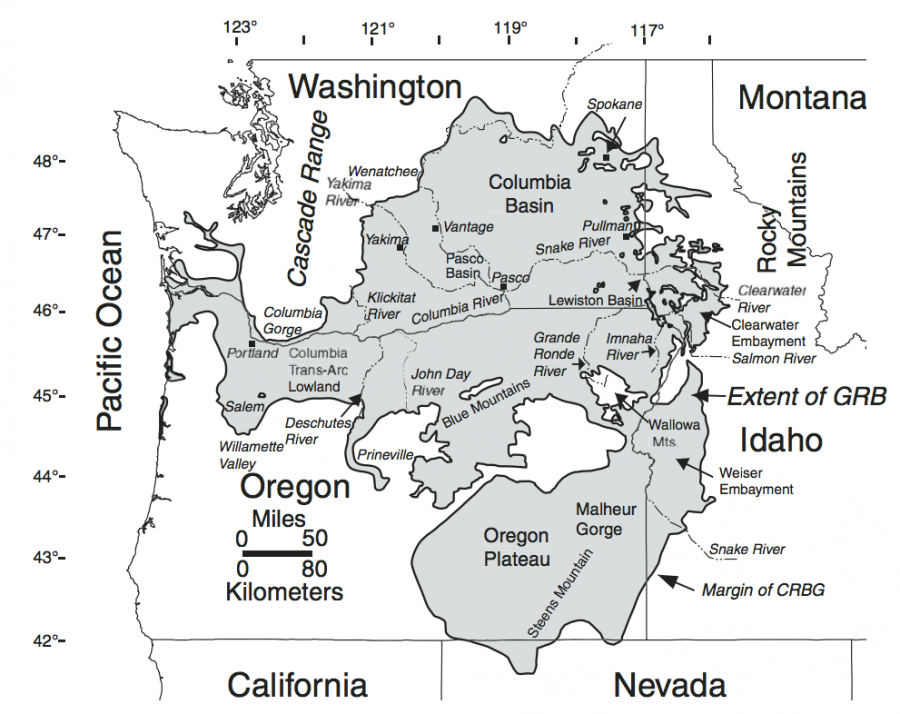

[00:10:05] Mark Amara: Yes, that’s a great question. The Columbia Plateau is an area where lava erupted over millions of years, between 6 and 17 million years ago.

It is made up of massive volumes of lava that erupted from cracks or fissures in the earth’s crust. The Columbia Plateau is represented by most of north-central Washington, the west part of the north Idaho Panhandle, and northern Oregon. And it covers about 63,000 square miles in that area.

There were virtually hundreds of flow events. And they’re stacked up, if you can imagine it, like layers in a cake. And you can see that those layers are represented quite visually in the Grand Coulee if you’ve ever driven up that way. In some places, the bedrock layers are stacked one on top of another and exceed more than two miles, like in the center of the Pasco Basin.

Also, north of the Columbia Plateau, the Okanogan Highlands consist of igneous magma or lava, that did not surface and formed large granitic masses that were exposed through erosion. You can see them now exposed up in that area, and cover most of northern Grant, Douglas, and Okanogan counties. The region is capped with windblown silts called loess and ash or volcanic tephra from volcanic eruptions.

What are Coulees?

[00:11:49] Erin Landon: Okay. Oh, you mentioned, um, coulees and it wasn’t until recently that I realized that that was actually a geologic formation. Can you tell us a little bit more about what a coulee is?

[00:12:00] Mark Amara: So coulees are kind of canyons or ravines that form. Um, they’re actually in this area, they’re the result of erosional events that occurred by catastrophic flooding from the Missoula floods.

An Overview of the Missoula Floods

[00:12:20] Erin Landon: Okay. Well, that’s a good segue right into the Missoula floods, which is what I wanted to ask you about. So, can you tell us, start off by telling us kind of an overview of what the Missoula floods were?

[00:12:31] Mark Amara: Sure. The Missoula floods originated as a lobe of the continental ice sheet that blocked the Clark Fork River in Northeastern Idaho and impounded a gigantic ice dam.

It created a gigantic ice dam that impounded a lake that was over 2,000 feet deep, covered over 3,000 square miles, and occupied a volume of more than 500 cubic miles or one-fifth the size of Lake Michigan. Several times during the last 2 million years, the dam holding the water back was breached, causing sediment, ice, rock, and water to explode literally downslope to the west through the Clark Fork and Pend Oreille Valleys down the Spokane Valley, into the Spokane River, into the Columbia River, to outlet eventually into the Pacific Ocean.

It’s believed many of the early floods were pretty much confined to the Columbia River proper. It’s only the most recent floods, the floods between 14 and 20, 000 years ago, that were diverted out into the Columbia Plateau.

[00:13:42] Erin Landon: So, and so it was the outflow of those floods that helped carve the coulees?

[00:13:48] Mark Amara: Yes, they, the coulees that were created in the Cheney-Palouse scablands and the Grand Coulee and Crab Creek and several other, there were several flood channels that, that emptied into, for example, the Quincy Basin. So we had the Grand Coulee, which is the longest, deepest, and widest channel.

Then there was Crab Creek, which also emptied in the Quincy Basin. The Bowers Coulee, Esquatzel Coulee, and Lind Coulee all emptied into the Quincy Basin. And what’s interesting is that as all these flood channels converged on the Quincy Basin, the Quincy Basin completely filled up and the outlets were not sufficient to release the water all at once.

So it backed up into the Quincy Basin, the area between the Saddle Mountains to the south and the Beezley Hills on the north end, just north of Ephrata. So that area completely filled up and the outlets were not sufficient to release it all at once, so it created huge inland lakes.

There were eventually outlets created through the Drumheller Channels, which are another series of coulees and Lower Crab Creek which eventually reenters the Columbia River. And, there were three outlets north of the Frenchman Hills at Crater Coulee, Potholes Coulee, and Frenchman Springs Coulee. And those are all coulees that can be, you know, that are easily accessed now.

[00:15:25] Erin Landon: So would the lakes, the inland lakes, would that have been like, like Banks Lake and in that area or…?

[00:15:32] Mark Amara: No, that it would have been farther to the south, south of Soap Lake. So as, as material exited the Grand Coulee at Soap Lake, then it entered the Quincy Basin, which was, you know, a low-lying area.

[00:15:47] Erin Landon: Okay. So in, does this, the floods are what created what we now know of as kind of as the channeled scablands? Is that the whole overall?

[00:15:56] Mark Amara: Yes.

[00:15:57] Erin Landon: So how did all of that sediment and the outflows of the floods, um, alter the soil composition?

[00:16:06] Mark Amara: The Missoula floods were significant in that they plucked and gouged the landscape throughout Eastern Washington, where erosion occurred it exposed bedrock. And that’s the basalt bedrock. So the soils in those areas are shallow or moderately deep over basalt. And where the floods deposited silt, sand, gravel, and boulders, it’s much deeper. In some areas where slack water lakes form, those are the lakes that backed up like into the Quincy and Pasco basins.

The soils are relatively rock-free and finer textured, though they may have accumulated what is called erratic rocks embedded within them. The Channeled Scablands exhibit a whole range of features like basin and butte, topography, goat islands like steamboat rock, deep coulees and canyons, mesas and hanging valleys, alluvial fans, gigantic gravel bars, ripple marks, slack water and lake deposits, a whole range of features.

The soils are generally shallow and scoured or gouged areas where bedrock is exposed, while there are thick deposits, hundreds of feet thick, of coarse-textured, sandy, gravelly, and bouldery flood deposits and finer-textured lake and slack water deposits.

Floodwaters and Our Coast

[00:17:34] Erin Landon: Okay, so as that those floodwaters move down into the Columbia River, my understanding there’s a lot of material, so much material came down the Columbia that it basically continued to, uh, is it what worked its way up the coastline?

[00:17:49] Mark Amara: There was so much material that was dumped into the ocean, that it did affect the ocean currents. It was pretty much just created a huge alluvial fan out in the ocean.

[00:18:04] Erin Landon: Timing speaking, I’m not sure how the Cordilleran Ice Sheet, I don’t remember if that was before or after the Missoula floods, but, um, that had more influence on the west side, correct?

[00:18:16] Mark Amara: The Cordellian Ice Sheet, was part of the glacial activity that that dominated the continent in Washington state, in the last 2 million years until the last 12 to 14,000 years when the glaciers permanently retreated. The continental ice sheets were part of the events that caused their advances and retreats of the glaciers four to six times during that 2 million year period.

So once the glaciers retreated and post-glacial flooding ceased, sediments were deposited on top of the glacial deposits in Western Washington, many of the soils that I dealt with have dealt with over there, have hard pans in them, and that’s what’s created by the immense weight of the glaciers on the landscape, in many parts of the state since the glaciers retreated, um, post-glacial flood sediments are capped with more recent alluvium, that’s volcanic ash and windblown silts called loess, the Palouse region is, a good example of that, of those windblown silts.

Basic Soil Forming Factors

And it’s, it’s kind of interesting that different soils form in different ways. Um, Western Washington versus Eastern Washington. There are five basic soil-forming factors, and those are parent materials, climate, relief, organisms, and time. All soils form in parent materials, vary by climate and relief, and are influenced by plants, animals, and human activities over periods of time, so they’re all different and it depends on all those factors interacting with each other to get a particular suite of characteristics

Understanding Local Geology and its Impact on Soil Composition

[00:20:37] Erin Landon: That makes sense so, um how can understanding our local geology help our knowledge of the our soil properties and the composition of the soil?

[00:20:51] Mark Amara: Okay. Recognizing and learning about the geologic formations and parent materials from which soils form can be helpful in determining what options there are in managing soils in our gardens and yards. For example, much of the Columbia Basin is in a low rainfall, high wind area, with parent materials that consist of alluvium, wind-blown sediments, volcanic ash, flood deposits, and lake sediments, which overlie basalt bedrock.

Knowing a little about the geology or stratigraphy which was my field of study, which deals with depositional processes and rock strata that occur in the earth’s crust, whether deposited by wind, water, ice, or lava, and seeing that soils in Eastern Washington consist of a lot of sand, sandy loams, and silt loams derived from various sources that erode easily If they’re not adequately covered can help determine management options.

Shallower soils over basalt bedrock or those with water tables or other restrictive features like hard pans have more restrictions on use and management than deeper soils. So using practices like residue management, building organic matter with cover or green manure crops, compost or mulch, growing native and drought tolerant resistant plants, and using crop rotations and minimum tillage can help minimize wind and water erosion.

In the Palouse or higher rainfall areas, using these same practices helps soils from washing off down slopes or leaching during wet areas. These same practices are applicable to anyone who gardens to help build soil tilth, keep it from eroding, and keep it healthy. Other practices like nutrient and pest management and irrigation water management are also important and can help keep soils productive and in place.

Relating to soils has been kind of an easy way for me to help connect the public to issues in their yards and gardens. And so I depend on soil information as kind of the building block or the foundation of a lot of what I focus in on.

[00:23:11] Erin Landon: Okay, that’s great. I know in our area, we’re in the Chehalis River Valley, and so we have very gravelly loam.

Okay, right. And some of the rocks are quite large, so it’s very, very fast-draining soil. And so if you’re not careful, you’ll just wash all your nutrients right through the soil every year.

[00:23:30] Mark Amara: And this is true.

[00:23:32] Erin Landon: So that’s, that’s the challenge of where we’re at and with our soil type.

[00:23:37] Mark Amara: yeah, I’m on flood deposits myself.

So, Missoula flood deposits, and it’s a very rocky soil. It’s, it’s quite a challenge. I’m always picking rocks.

The Columbia Basin Irrigation Project

[00:23:48] Erin Landon: Uh, so you mentioned, um, irrigation, so what is, can you tell us a little bit about the Columbia Basin Irrigation Project, or, and, uh, the impact that it has on the soil and water management?

[00:24:01] Mark Amara: The Columbia Basin Irrigation Project was an irrigation project that was authorized in 1935, and it began delivering irrigation water, power, and flood control in the Columbia Basin beginning in 1952.

There are over 70 different kinds of crops grown on nearly 700, 000 acres of land in a bunch of counties, Adams, Douglas, Franklin, Grant, Lincoln, and Walla Walla counties. So water is pumped, about 3 percent of the Columbia River volume is pumped out of the river at Grand Coulee. And, it fills reservoirs, canals, laterals, drains and waterways throughout the area. The result of some of those canals and laterals are lined, but most are not. And the water table has risen in many areas over 150 feet higher. Before the introduction of irrigation water, farming, and gardening depended on wells and annual rainfall.

And in our area, we’re in a 6 to 9-inch annual rainfall zone, so it was pretty desert-like. With guaranteed availability of irrigation water, the desert has been turned into an oasis. The Columbia Basin has been transformed into one of the most productive farming and growing areas of Washington.

Many soils that were once dry now have water tables and can’t be farmed.

Others are sub-irrigated and require little irrigation. Irrigation systems, at least on the farmland, have changed from rill, gated pipe, and flood irrigation to much more efficient irrigation systems using sprinklers and drip irrigation, which uses water more efficiently and reduces runoff and leaching of soils and fertilizers.

As water shortages and costs affect nearly everyone here in the Columbia Basin, using irrigation water management practices and drought-tolerant or native plants is becoming more of a necessity.

How to Use the Web Soil Survey to Determine Soil Composition

[00:26:12] Erin Landon: So I know a tool that I’ve used is the Web Soil Survey, and I know that’s put out by the USDA, the NRCS. So can you tell us a little bit about it and how home gardeners can utilize it to understand their soil composition?

[00:26:30] Mark Amara: Yeah, I really depend on Web Soil Survey a lot. It’s a wonderful tool for gardeners. People can learn about basic soil properties of the land that they manage or they own. It’s web-based. It provides maps and descriptions of soils all over the U. S. And it’s, and you access it by address. You can put in your personal address, section, township, and range, soil survey area.

There’s a whole suite of ways to access it. Soil scientists working cooperatively through agencies, universities, and the agricultural resource service mapped, are mapping or, or updating soils across the U.S.

I was one of the USDA NRCS soil scientists who mapped soils in Grant and Clallam Counties.

Learning about the soil, and basic soil properties that make up any property are great ways to learn about soil properties and help guide people to maximizing its potential. Properties like parent material, position in the landscape, drainage, texture, coarse fragments, depth to water table or bedrock. Others are really helpful and provide baseline data for all gardeners on using and managing their soils.

More specific information is also available like water holding capacity, shrink swell potential, plasticity and consistency, pH, vegetation, use and management, and interpretations for different uses. When I worked for NRCS, that was my career, was through NRCS. I informed farmers and ranchers about soils.

Since I’ve been a master gardener, educating the public about soils and providing soil information to individuals have been easy ways of connecting to clients. And everyone seems receptive to learning about soils and ways to better manage them.

[00:28:32] Erin Landon: Yeah, the Web Soil Survey was how when we first bought our property, we used that to know what we were getting into and what the soil composition was.

So we knew going in that it was gravelly and, and fast draining. And, um, so we’ve been really working hard to build topsoil the last five years. So.

[00:28:51] Mark Amara: sometimes that’s, kind of an afterthought when one buys a house, to look at the soil type. But yeah, building organic matter is, seems to be a continual process.

[00:29:03] Erin Landon: So, and my understanding, so, the Web Soil Survey is going to apply to native soils. So say if you live in a housing development or there’s been a lot of, there’s disruption of the soil, disturbance thing, um, it may not be totally accurate. Is that correct?

[00:29:22] Mark Amara: That’s correct. And, and often, the soil surveys are accurate. It depends on the intensity of the soil surveys that were done. It may be accurate down to about 10 acres. In the best situations, unless a more intensive survey was conducted, and that’s often not the case. So it’s a tool, but it’s not the final word. Ideally, you know if you want to figure out what the situation is in your particular plot, soil testing is the best way, is a good way to find out what the existing conditions are and then work from there.

[00:30:09] Erin Landon: And if I remember right from my training, which was almost 10 years ago now, um, you can do, like if you put a soil sample in water and shake it up and it’ll settle out, right? So you can kind of see the proportion of…

[00:30:23] Mark Amara: distribution of sand, silt, and clay, yeah.

[00:30:27] Erin Landon: Uh, let’s see. I think that covers my questions. Is there anything that you’d like to add?

Final Thoughts on Geology and Soil Composition

[00:30:33] Mark Amara: No, this has been actually pretty fun.

[00:30:36] Erin Landon: Well, thanks for joining me today. It was a great conversation and I hope everybody learns a lot about Washington geology.

[00:30:44] Mark Amara: I hope it’s helpful for everyone. I appreciate your willingness to work with me on it.